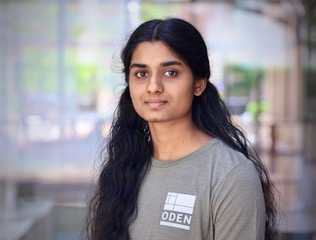

While most engineers predict effects from causes, undergraduate and two-time Moncrief Intern Arushi Sadam is flipping the script: developing innovative methods to infer causes from effects. Called “inverse problems,” they have applications spanning tumor detection, tsunami warning systems, and locating underground oil deposits. But this thread of ‘flipping the script’ has woven throughout Arushi’s entire life.

Homeschooled as a child, she learned early — through the freedom of building her own curriculum — that she could take control of her education, following her curiosity into niche topics and new fields rather than being confined to a preset path. This attitude has carried with her following her transfer from Texas A&M University to The University of Texas at Austin in 2023, through two summers in the Moncrief Summer Internship at the Oden Institute for Computational Engineering and Sciences, and as she continues to forge her path toward a career in solving inverse problems.

“I was able to take math and science classes as fast as I wanted,” Arushi reminisced about her homeschooling years. As long as she fulfilled basic requirements, she could piece together a curriculum from a mix of self-studied courses and community college classes to learn whatever piqued her curiosity. With this arrangement, she was able to rapidly progress to advanced STEM classes such as Linear Algebra and Differential Equations.

Now, as a senior in college studying computational engineering, Arushi continues to explore a wide range of STEM topics, but instead of stacking a bunch of classes in her schedule, she has accomplished this exploration by immersing herself in diverse research environments. “I am not doing any minors. Instead, I’ve been doing research with different purposes.”

Her first research gig was coding for a psychology lab during her freshman year, which sparked her interest in machine learning and optimization problems. Her next position as a sophomore at UT was developing nonlinear finite element solvers to investigate truss structures. Then, in 2024, she was accepted into the Moncrief Undergraduate Summer Internship Program, a ten-week, paid opportunity to conduct computational research with a faculty member at the Oden Institute.

There, Arushi spent the summer under the mentorship of Michael Sacks, professor of biomedical engineering and director of the Willerson Center for Cardiovascular Modeling and Simulation at the Oden Institute, where she got her first glimpse of inverse problems. In contrast to forward problems, which predict effects from causes and are governed by partial differential equations (PDEs), inverse problems predict causes from effects. Typically, inverse problems predict a PDE’s parameter field, boundary condition, or initial condition (the cause) from data (the effect).

Under Professor Sacks, Arushi simulated the activation of aortic valve cells in a tissue-mimicking gel based on how samples from the gel moved due to the activation. From the samples’ motions, her job was to work backwards and infer how the stiffness inside the gel had changed, essentially using displacement data to reconstruct a hidden stiffness field.

Arushi reflected on this opportunity, “Back then, I really did not know much about inverse problems, so it was nice to see the optimization algorithms you could use.” But she was not satiated: she craved digging deeper and learning more about the methods underlying these inverse problem solvers. “We were trying to make the inverse problem solver faster by using a GPU-based code. Personally, I felt like speeding up applications using basically the same methods was not going to be fast enough.”

In summer 2025, Arushi returned to the Oden Institute in her second stint as a Moncrief Intern. She worked with Omar Ghattas, Oden Institute principal faculty member and mechanical engineering professor. This time she was pursuing a more ambitious goal: solving the inverse problem instantaneously. In standard methods (like the one she implemented over the previous summer), “you collect some data from a system, and then you have an iterative solver,” she explained. Recovering a stiffness field from displacement data, for instance, traditionally requires solving the PDE thousands of times to converge on the correct parameter field, which can be very expensive and time-consuming.